By Jacob Waiswa Buganga

Poverty is responsible for the plight of children Worldwide. In Africa, only 16 percent of the children in Africa have social protection. The 2016 Children’s Act 4(4) of Uganda underscores the right of children to live with their loved ones, have a nationality, be safe and access social services, be treated without any discrimination of any kind, and access effective legal aid in all legal proceedings brought against them.

However, according to the 2014 census, substance agriculture was close to 70 percent.This means that households were unable to have income to cater for the needs of their children. Migrations to cities proved to be the best alternative for them, because rural poverty is greater than urban poverty. In cities, street children live in incomplete building structures, drainage channels, under bypass highways, verandas of closed shops, and broken-down vehicles. Collaborating evidence from UNICEF report 2012, reported that street children lived in basements, bridges, and open-air spaces.

This article contributes priority considerations for transforming lives of street children, basing on current needs and interests to design short-term, mid-term, and long-term interventions that support aspirations towards sustainable healthy growth and development, and realization of their full potential. The sought to understand how street children navigated broken family life and street life in cities without families, using a case of Kampala City.

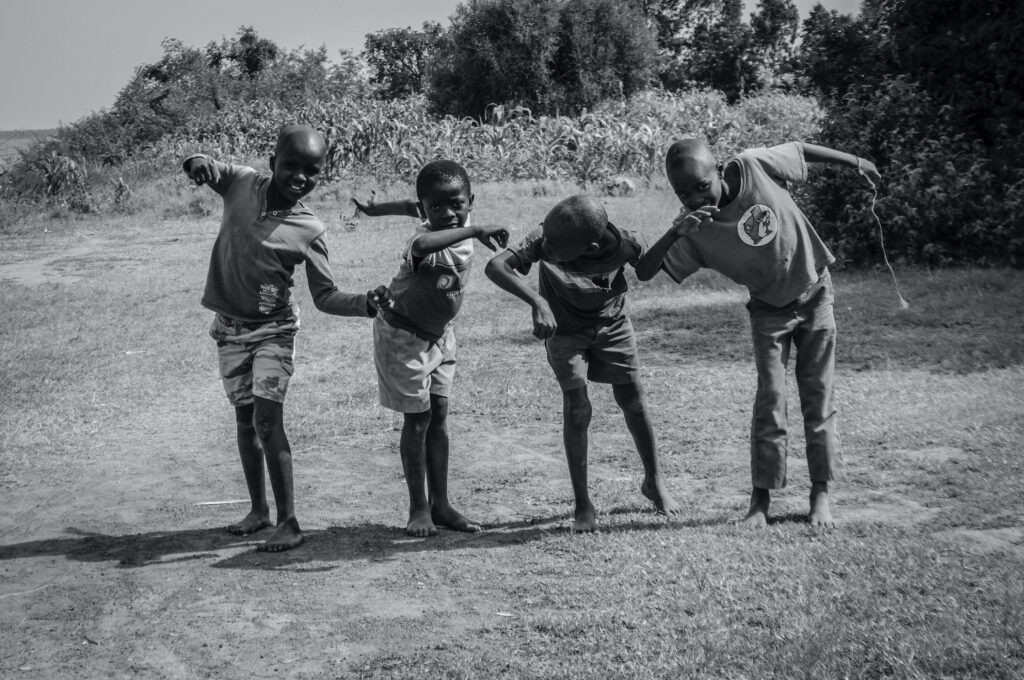

Fifty street children between 5-17 years took part in the study. The conditions at home were revelations of a combination of poverty and violence, because of frustration from failure of parents to meet their family obligations. Hence, children lost meaning of family life and sense of belonging to their respective families. Navigating uncertainties in cities for prospects of better life was their only option.

Further, they faced violence in unprotected neighborhoods, worst forms of violence, and exploitation on streets. Street children collected (‘kuwenja’ is commonly used word by them to means ‘relentlessly find’) scrap, and they took on roles, such as washing dishes, unloading trucks, car washing, and car-turn guides for a livelihood. Then, a category of street children who join gangs (‘kasolo boys’ – a criminal outfit category of street children) for own security against other hostile groups, relied on crime for survival regardless of the risks to injury and death.

Behind the activities they do are adults, who exploit them in exchange for food and for less than a dollar per kilogram of scrap (between 5 and 15 US dollar cents per activity and kilogram of scrap, respectively). The study found evidence of sex abuse of street children perpetuated by older boys against much younger children as young as 5 years. On the other hand, girls took on prostitution as main source of livelihood. Despite efforts by non-state actors and well-wishers to adopt and offer meaningful care and support them, they did that in vain.

Conduct problems were so deep in the lives of street children and were not part of city plans of service delivery. As such, street children preferred to grow up in the world of work and creating endless avenues for survival and livelihood development. Poor families coped negatively by neglecting children, which climaxed into extreme violence.

On the streets, children drew resilience from the fact that the return home was never an option. Sometime street children collected useful ‘scrap’ without permission from mainstream class of dwellers, who interpreted it as an act of theft. This heightened anxiety among mainstream urbanites, who in return became hostile towards them. The street children expressed compatibility to flexible education system that integrates wage-rewarded work and some of absenteeism.

Street children demonstrate ability to adapt to new situation and fit well to survive. There were sympathizers within slum areas, who mutually benefitted from child labor and crime involving street children. Good Samaritans, who attempted to adopt street children, faced conduct problems and antisocial disorders, rendering latter unfit to live among foster families and ‘normal’ lives as other children. They often escaped back to streets.